Diffusion, Fick's laws, and the importance of conservation laws in non-steady state processes

Here we derive Fick’s first and second laws of diffusion, and illustrate the importance of considering a conservation law when considering non-steady state processes.

What is diffusion?

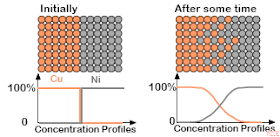

We will consider diffusion as meaning the phenomenon of material transport by atomic motion. Diffusion really is a simple process to understand that goes back to something you probably heard in a high school physics or chemistry class: particles move from high concentrations to low(er) concentrations over time. Now there are many different kinds of diffusion depending on the material’s phase (solid, liquid gas) and Fick’s laws are applicable to each, but it will be easier for us to fix one example in our minds; to this end, let’s think of a copper (Cu) - nickel (Ni) diffusion couple. This is an example of solid diffusion. Now solid diffusion will happen (albeit very slowly) at any temperature, but usually how this works is two bars or ingots are brought into contact with one another and heated for an extended period of time (but below the melting temperature of each) and cooled back to room temperature. Perhaps now is a good time to also recall that there is a positive relationship between temperature and diffusion; at higher temperatures, the vibrational energies of the atoms increase, and these atoms become capable of diffusion. The more atoms which are capable of diffusion, the more diffusion that happens.

So now let us also recall that this diffusion process can be modeled in terms of the concentration of each of copper and nickel. When the ingots are first brought into contact with one another, the concentration is 100% copper and 100% nickel; you have two different bars of metal. However, as time passes, some atoms from the copper ingot migrate over to the nickel ingot, and some atoms from the nickel ingot pass into the copper ingot. At finite time, we still have pure copper on one side and pure nickel on the other, but now there will be a layer between the two with some copper and some nickel atoms. This can be modeled with a concentration profile, where the concentration of each material is placed on the y-axis and position (within the material) on the x-axis:

Again, this is a very simple introduction to the process of diffusion in materials science, and we note here that the actual physical processes involved here at the atomic level are in general more complex. We next present some of the mathematics used to model diffusion processes.

Fick’s first law

We are now ready to present Fick’s first law, the "easier" of the two laws to understand. Before we present the law, we first recall the idea of flux. By flux, we roughly mean movement through any given boundary or surface. In materials science, flux in the context of diffusion means the rate of mass transfer. The rate of mass transfer, or again, the flux, is defined as the mass (or the number of atoms) $M$ diffusing through and perpendicular to a unit cross-sectional area of solid per unit of time. This may sound technical, but just think of the number of copper atoms passing through the copper-nickel interface per second.

Now of course the flux has a mathematical representation; we will denote it with $J$. We can write the flux as

\[J = \frac{M}{At} \tag{2.1}\]where $M$ is the mass of the material (in $kg$) or the number of atoms of the material (in $mol$), $A$ denotes the area across which the diffusion is occuring (in $m^2$), and $t$ denotes the elapsed diffusion time (in $s$). Consequently the units for $J$ are $\frac{kg}{m^2\cdot s}$ or $\frac{mol}{m^2\cdot s}$.

Before we proceed further we note here that Fick’s first law applies to the process of steady-state diffusion, and this is what differentiates its use from the second law. By steady-state, we mean that the diffusion flux is the same for all time $t$; think of this as a steady "flow" of atoms out of one material and into another for all time. Obviously, this is a big simplifying assumption for most diffusive processes, and we examine non-steady state diffusion below.

We’ve now arrived at the law. The mathematics at hand here is really quite simple. Let us denote the concentration of a material by $\rho$; it has dimensions in units of amount of substance per unit volume. Fick’s first law postulates that the concentration gradient $\frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}$ is proportional to the flux $J$:

\[J = -D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}, \tag{2.2}\]where $D$ is the diffusion coefficient or diffusivity; it has units in area per unit time ($\frac{m^2}{s}$).

What (2.2) establishes mathematically is exactly that particles move from high concentrations to low concentrations. Notice that as the concentration gradient $\frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}$ increases, representing a more rapid change in the concentration of the material, the flux $J$ also increases. Again, this means more atoms are moving throughout the material, and so we get more diffusion. On the other hand, when $\frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}$ decreases, this means the concentration of the material is changing less rapidly. Consequently, the flux decreases, and there is less diffusion.

Before discussing Fick’s second law, let us note here that (2.2) above describes steady state diffusion in one space variable (e.g., along the $x$ direction). In this case, the flux $J$ is a vector field, and (2.2) becomes a partial differential equation:

\[J = -D \nabla \rho.\]For simplicity, we will consider only the ``1D” case here.

Fick’s second law

We are now ready to discuss Fick’s second law, which deals with non-steady state diffusion. This means that the diffusion flux and concentration gradient vary with time. This is the behavior which is expected for most cases of diffusion. For instance, think about releasing the pressure valve on a pressure cooker: upon release, you immediately hear a rush of pressurized air diffusing out of the pressure cooker, but then you hear this rate gradually taper off until the pressure inside the cooker is equal to the pressure outside. Here the rate of diffusion decreases with time.

Conservation laws in non-steady state processes

So how does the mathematical representation of non-steady state diffusion differ from (2.2) above? Since we are now in the case that the diffusion happens at a different rate depending on time, meaning that atoms/mass is flowing through the material at a different rate depending on how far along we are into the diffusive process, we need to think about a conservation law. The important quantity to conserve here is mass; we need to make sure that our equation describing non-steady state diffusion does not add or delete mass over time. Using the same notation as above, a conservation of mass law can be stated as follows:

\[\partial_t \rho + \frac{\mathrm{d}J}{\mathrm{d}x} = 0. \tag{3.1}\]What (3.1) roughly says is this: for any fixed region within the material and any time $t$, the rate at which concentration changes with respect to time ($\partial_t \rho$) is equal to the rate at which the diffusion flux is changing ($-\frac{\mathrm{d}J}{\mathrm{d}x}$) across that region at time $t$. Stare at the definitions and equations for awhile and you can convince yourself that again this is just an idea from high school science class.

This derivation of (3.1) illustrates something actually really mathematically significant. Whenever we are dealing with a physical process (e.g., diffusion, chemical reaction, etc.) that changes in some way over time, we must think of quantities we need to conserve (e.g., mass, energy, electric charge). These will all require some sort of conservation law in our model for the physical process at hand. For example, in (3.1) the change in concentration with respect to time ($\partial_t \rho$) is exactly balanced out with the flow of mass out of the material ($-\frac{\mathrm{d}J}{\mathrm{d}x}$); this ensures that we are not "creating" or "deleting" mass as time varies.

Conservation law to Fick’s second law

The question remains how to relate our conservation law (3.1) back to in terms of the concentration $\rho$. To this end, let us recall Fick’s first law (2.2):

\[J = -D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}.\]Differentiating both sides with respect to $x$, we find

\[\begin{align} \frac{\mathrm{d}J}{\mathrm{d}x} &= -\partial_x\Big[D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}\Big] \tag{3.2} \\ &= -D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}^2 \rho}{\mathrm{d}x^2}-\frac{\mathrm{d}D}{\mathrm{d}x} \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x} \nonumber. \end{align}\]Finally, inserting (3.2) into (3.1) gives Fick’s second law:

\[\partial_t \rho = -\frac{\mathrm{d}J}{\mathrm{d}x}= \partial_x\Big[D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho}{\mathrm{d}x}\Big]. \tag{3.3}\]We conclude with one final remark. The coefficient of diffusion $D$ in general depends on $x$. This means that the material has different diffusive properties at different locations within the material. This corresponds physically to an anisotropic material, one where we see a lot of variation in grain size and structure depending on where we’re located within the material and which direction we look in. If our material has a high degree of isotropy, meaning that the size and structure of the material is roughly the same in all directions, then it makes sense that the properties (such as diffusivity) of the material will also roughly be the same in all directions, and we may assume that $\frac{\mathrm{d} D}{\mathrm{d} x} =0$. In this case, (3.3) becomes

\[\partial_t \rho = D\cdot \frac{\mathrm{d}^2\rho}{\mathrm{d}x^2} \tag{3.4}.\]You might recognize this as a 1D heat equation. This implies that heat transfer within a material behaves very similarly to diffusion, and in fact, we may think of heat transfer within a material as an example of diffusion (in the sense that higher temperature areas diffuse to lower temperature areas and vice versa) inasmuch as we are willing to accept that energy is equivalent to mass.

References

- William D. Callister, Jr. and David G. Rethwisch, Materials science and engineering: An introduction, 10th ed., Wiley, Hoboken, 2018.

- University of Auckland, Conservation of mass.

- Wikipedia, Continuity/transport equation.

Image

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=http%3A%2F%2Fdiffusioninsolidsees.blogspot.com%2F2010%2F05%2Fdiffusion-phenomenon.html&psig=AOvVaw1EmBi8mLhMpdgVysUVN-Ed&ust=1757557826532000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBkQjhxqFwoTCKjb4rSYzY8DFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE